David Buchan: Modern Fashions (1981)

This review never had a final edit because, in the end, I decided not to publish it—perhaps because I didn’t think it was sufficient as a critique, or because I didn’t want to criticize a friend. Obviously, I changed my mind about the work. In 2014, the complete series had pride of place in my exhibition Is Toronto Burning?—Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene.

David Buchan Mercer Union, Toronto February 17 - March 17, 1981

David Buchan based Modern Fashions on men's advertisements mainly from Esquire magazine of the years 1959–63. The works’ “theoretical” base could be called a strategy of inhabitation. Inhabitation’s theoretical origins are aligned to Derrida’s deconstruction, Barthes’ textual pleasure, and in a vague way to “Anti-Oedipus”; its artistic practice in Canada has been defined and exploited over the years by General Idea. The difference between General Idea and David Buchan, on whom an influence has been exerted, is that Buchan closely adheres both to the format and given image, slipping himself into it as if into a role (performing the message), and diverting the received text to his own ends. The resulting ensemble is less fictive, less totalizing than General Idea’s pavillion thematics; but similar to this collective, Buchan attempts to create or effect a discourse through the mechanisms of this format within art.

The context of this work, divorced from the page and hung in a gallery (the work includes a publication/catalogue of the photo-texts), is art, not the original medium of the sources’ presentation: the work inhabits a form not the original context of a mass magazine, which raises the question of its audience and intention. Attention may be paid to the intention of the context: on the one hand, to an analysis of intention or meaning that usually does not take place in advertising (that would reveal advertising’s mechanisms); on the other, to the message within an art discourse—a discourse become art process.

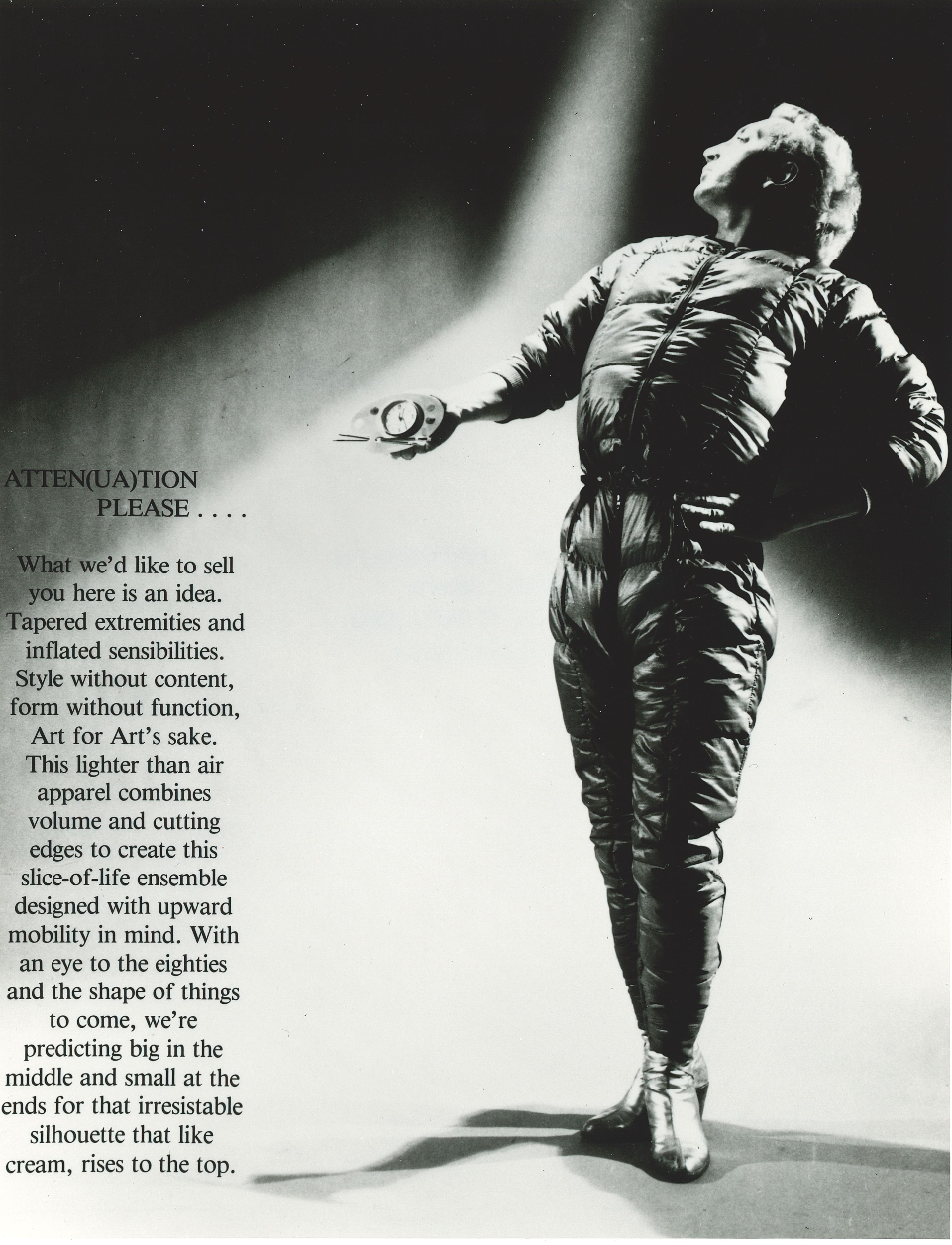

To say intention is to say an “I” who intends; but where is the “I” here when the artist inhabits/performs all these different identities. Since the work is not an analysis of advertising, the point is to analyze the strategies that may be drawn from it: an advertisement for art ("What we like to sell you here is an idea," reads the prologue Atten(ua)tion), or display of artistic codes of operation.

The full title of the exhibition is Modern Fashions, or an Introduction to the Language of Partial Seduction. It states “partial seduction” because in order for fashion to work, and to reproduce itself in time, there must be both an attraction to buy—a garment, a form, an idea—in the first place and a willingness to let that fashion go in time for the next. (The theme of time runs through the exhibition; the opening panel and cover of the publication states: "Killing time? know Sixty seconds to a minute ... sixty minutes in an hour... You the rest of this story, but who knows where the time goes? Try and track it down, try and stop it in its tracks. You can beat the clock, but you can’t kill time. The solution? Sit back and relax in Modern Fashions.”) The irony of the artist is his partial attraction and seduction, like the dandy flaneur who inhabits a crowd but is detached as an observer. Attraction and distraction regulate the production and display of the work: standing in front of an image and moving to the next, or flipping through a magazine are the models for its organization.

Identification and movement, or, in other words, metaphor and metonymy, bring the organization of the work in the exhibition to the model of language; as Buchan says, it is a language of partial seduction. Fashion can be thought as a language code with its formal symmetries and inversions and interchangeability of elements. For example, the panel Au Contraire, contemporary fibres contrasts high and low culture fashion elegance, in black and white inversions. The texts “oppose” each other, each directing a reading of opposition or attraction between the male figures: the image mx can carry any content according to the text.

While the elements of the code float interchangeably, for the purposes of selling an image or idea must stabilize, that is, become identifiable. The individual creates himself or herself after this image, or positions himself/herself as an operator of the code. Either the code securely establishes meaning or identity, as in Men like you like Semantic T-shirts, or the code becomes self-reflexive in inhabitation/assumption: "This self-reflexive statement of the nature of compulsive self-identification in the latest style in self-addressing. His fetish, why the Semantic T-shirt,” states another part of the same panel.

As the panels do not necessarily refer to advertising, they constitute a discourse on art. If the shoe fits—Wear it playfully mocks the consumption or display of theory (as identity between work and theory)—the shoe as “support structure.” Cam-o-flage Brand Underwear elaborates a disguised strategy—that of inhabitation. Atten(ua)tion Please announces what is to be sold—an idea of art rather than a garment. Referential to a garment worn by the artist, the text the proliferates cliches on art sensibilities.

Yet, it is that seemingly effortless proliferation within language, within the codes of art and theory, that is problematical. As an entertainment, the exhibition is witty and intelligent; but to what end is the display of codes and the discursive elaboration of a discourse that undermines itself? What is the effect when the mastery of a code turns into the formal language of a genre? Inhabitation was assumed as effecting a disguised discourse within another conventional language for the purpose of critical disruption. Can inhabitation be critical at all, except through exacerbation—that is, as a symptomological analysis? When these theoretical effects energetically emerged in translation in North America they were productively grafted at a time when the discourse was already politically exhausted elsewhere. Productive and disruptive for individuals as a strategy in the late ’70s (Modern Fashion was first exhibited at the Glenbow Museum December 1979 – February 1980), its use has been played out and should be abandoned rather than retained as a form or device. Perhaps we have to pass from strategy to tactics, each in our own circumstances. After all, advertising is a tactic, not a strategy.