Carmen Lamanna Gallery (1966 - 1991): An Archival History

Material will be added to this site over time.

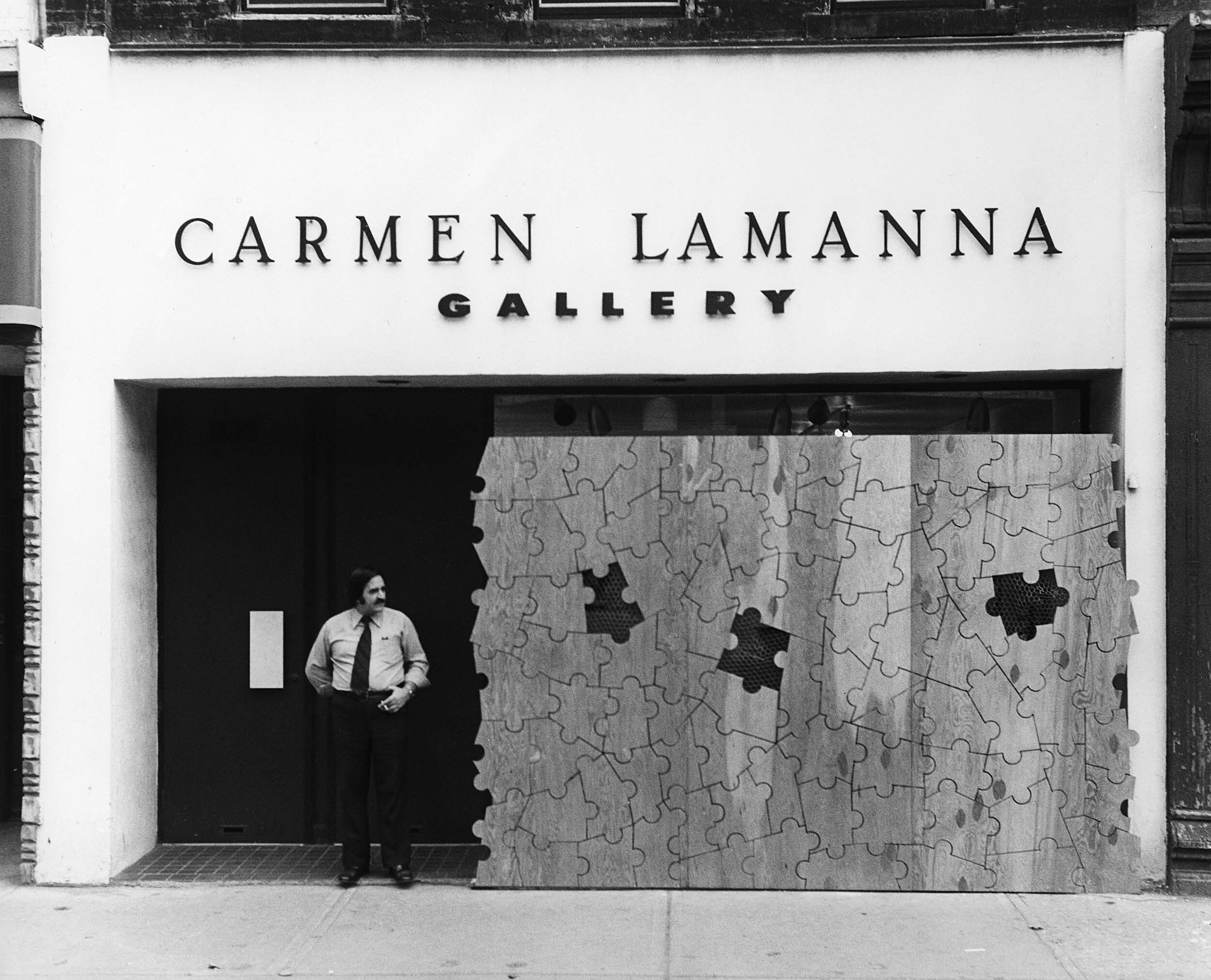

Carmen Lamanna Gallery with General Idea, The Hoarding of the 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion, 1975 (exhibited in Going Thru the Notions, October 18 – November 6, 1975). Photo: Henk Visser, courtesy Carmen Lamanna Estate

Part 1

The Legendary Carmen Lamanna Gallery

Is it legendary … or merely forgotten? That is, the Carmen Lamanna Gallery, which existed from 1966 to 1991. During those years it was the most important commercial gallery in Canada—and arguably more than just a private art gallery in its influence. Is its history lost? Writing about Carmen Lamanna’s legacy four years after his 1991 death, in an article that was as much about his entangled business affairs and deviously complicated relations with artists as it was his legendary status as innovative dealer, Adele Freedman ended with the warning, “Myths last only as long as people can believe in them.”

This being Canada, Freedman can’t claim any prescience in a place, after all, where history does not take readily, but roots itself insecurely in our glacier-racked, shallow soil. History is contrary to myth, but myth perhaps is all we have, and so must we secure it in stories that elaborate themselves eventually into what is acceptable as history. Carmen Lamanna is one of these stories.

Living as they do on air, myths therefore are important to grab hold of—even if you could say Lamanna, rather, contrarily sprang from the soil. No Apollo of the empyrean realms, Lamanna was more the Vulcan type, labouring in his earthly forge. Yes, of course, Vulcan’s forge was rumoured to be underneath Sicily’s Mount Etna, not a few hundred miles away under Mount Vesuvius, which was just to the west of where Lamanna was born in 1927 in the village of Monteleone. Indeed the volcano might be central to Lamanna’s self-myth as, for instance, when he wrote in a letter announcing the move of his gallery that had “developed into a unique and inspiring volcano with unpredictable and surging energy created by intellectually minded artists.” For anyone that was admitted to his basement lair on Yonge Street, it was the foul-smelling and noisy old oil furnace that was unpredictable and the surging energy was festering in the hundreds of banker boxes that beset visitors in those cramped quarters, ready to explode. Being there, it made you think of the opening scene of the film Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy: “Trust no one, Jim, especially in the mainstream” the paranoid and beleaguered British intelligence chief says to a spy summoned to his service flat buried under piles of tottering files. It was here, late into the night, that Lamanna’s little-known letter writing campaigns to the Prime Minister, the Canada Council, and all levels of bureaucratic officials was waged on behalf of contemporary Canadian culture—waged indefatigably by an immigrant summoned to Canada in 1951 presumably to labour in the bowels of the earth constructing Toronto’s new subway. After all, in Toronto, selling culture was a WASP prerogative.

Maybe it was a whiff of sulfur that compelled people to think in class terms when talking of “the man from Monteleone,” as the headline of a 1968 Toronto Star article named him. “You live here. Tell me,” asked Italian art critic Achille Bonito Oliva years later of Globe and Mail art critic John Bentley Mays. “Who is Carmen Lamanna? He speaks Italian like a peasant, he uses old-fashioned words you only find in comic books. He’s fantastic!” He might have created a rare stable of “intellectually minded artists” but he was still judged by his accent. “Lamanna still speaks with a heavy Italian accent and prefaces most of his sentences with the word ‘anyway’,” Gail Dexter wrote in 1968 and John Mays could still repeat this characterization twenty years later, though claiming differently that Lamanna ended most sentences with the word. “Anyway” was a sentence in itself.

Anyway, it all came down to his peasant hands. He was “the $27-a-week picture framer who made good.” It was the artisanal status that was stigmatic. “No one took Carmen seriously at all when he started the gallery. We knew him as a fine carver of antique frames and as a restorer,” said Dorothy Cameron in 1970. Having opened a framing shop on one side of Yonge Street in 1960, Lamanna took over Cameron’s gallery space across the street in 1966, when she abandoned dealing over obscenity charges laid against her Here and Now Gallery.

Ensconced in his “blue chip” gallery nearby, the suave, Saville-Row-suited cosmopolite Walter Moos still in 1977 could dismiss the rude peasant with his labourer’s fists. “For Moos, swimming elegantly in the mainstream of art, Lamanna is a vessel stranded in unsavory backwaters,” Adele Freedman wrote for Toronto Life. Yet in 1970, TIME magazine could write that Lamanna was “a man steeped in the gilded classical tradition of Renaissance and Baroque Italy…. Lamanna was the grandson of a gallery owner who specialized in 18th and 19th century painters. At age eight, Carmen stood on a specially made step at the gallery workbench.” Carrying those traditions to Canada, Lamanna nonetheless rejected both the gilding and the bench, though he used both to lever his ambition to reflect his personality in a roster of artists of “unquestionable individuality” committed to “pure experience” and an art whose intelligence was exposed through matter.

TIME magazine, December 7, 1970

Moos accused Lamanna of “playing the isms game to the hilt.” The occasion of the TIME article, seven years before Moos’s accusation, however, was Lamanna’s vindication, coming from Europe, of course, by means of an invitation to participate in the 3e Salon international de Galeries pilotes: Artistes et Decourvirs de notre Temps in Lausanne, Switzerland at the Musée cantonal des beaux-arts, then travelling onto Paris at the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris. The only Canadian gallery invited, it was generally received to be, as well, the most progressive—Lamanna the pilot of les galeries pilotes! “Il capitano,” Jean-Christophe Ammann, one of Europe’s elite Kunsthalle directors, called him.

Carmen Lamanna Gallery installation at Musée cantonal des beaux-arts, Lausanne, Switzerland, June – October 1970; courtesy Carmen Lamanna Estate

Part 2

The Commercial Gallery as Performative Institution

April 1976 Invitation Card

July 1981 Invitation Card

Carmen Lamanna was the Carmen Lamanna Gallery. Of course, its name says so. But Lamanna was more than an ordinary dealer, for what is an ordinary dealer but a seller of goods merely deemed artistic, whose name disappears when the shop closes. He was more than an extraordinary dealer, those influential in the centre of the art world such as Leo Castelli in New York. He was his gallery. He performed his gallery. His gallery was a performance. For Leo Castelli, for instance, it was not. One of Lamanna’s former artists claimed, “The gallery is his alter ego; it goes beyond the bounds of business,’’[Freedman, 1977].

By “performance,” I do not mean the egocentricity implied by this statement from his former artist, which is suggested as a problem. It seems Lamanna was not simply reduced to the commercial exchanges a gallery demands. Nor do I mean he was a “personality,” though for many he was. A personality could still conduct business. Lamanna put something else of himself into his gallery that was supplemental to the artwork exhibited, exceeding bounds. Surely, business should be conducted, but behind the scenes. Surely, an art gallery should be transparent—neutral, that is—to the artwork exposed there. It was, at this gallery, but at the same time the Carmen Lamanna Gallery expressed itself as an apparatus. For Lamanna, the gallery was not merely an alter ego but an articulation of itself, an expression of its functions treated creatively, inventively, and with humour. Most dealers think of all this merely as advertising. Not Carmen Lamanna, who had a need. Lamanna would find a radical formation for this expression.

Lamanna expressed himself through his gallery. His choice of artists was an expression of his personality. Together they compose an intellectual portrait of the man. (At least one could say this of the early years of the gallery.) But Lamanna as well had a need to be an artist, and he used what was available to him of the gallery apparatus—advertising, postcards, etc.—to fulfill this need creatively. His gallery was an early example of a performative institution.

Was this understood at the time? Not really. “He’s put his personality on the line in a way that some dealers would find distasteful, even vulgar,” Adele Freedman wrote in 1977.

Dealer as Performer

Self Portrait, 1969 (postcard)

1977 Postcard with Ian Carr-Harris But she taught me more, 1977

December 1984 Invitation Card with Carmen Lamanna signature

Back cover, FILE Vol. 5, No. 3 Spring 1982 X Ray Sex issue (photo: Jorge Zontal)

Carmen Lamanna, limited edition signature silver broach, edition of 10; collection of Philip Monk

Part 3

A Portrait of Carmen Lamanna

…

“He’s more than one person. I can even say he’s more than two.” Brydon Smith in Adele Freedman, “Guarding the avant-garde: the case for Carmen Lamanna, Toronto Life, December 1977, 226.

…

Part 4

Exhibition History

The Carmen Lamanna Gallery opened June 16, 1966 at 840 Yonge Street. The location closed in May 1987. The gallery then moved to 788 King Street West, opening there in November 1987 and closing in November 1991.

840 Yonge Street, Axonometric projection

788 King Street West, Axonometric projection

Selected exhibitions 1967 - 1978

Denis Juneau, Murray Favro, Royden Rabnowitch, Andre Theroux; December 1, 1967 - January 2, 1968. Photo: L. R. Warren; courtesy Carmen Lamanna Estate

Milly Ritvedst, David Bolduc, Jean Noel, Gary Lee-Nova; August 2 - September 25, 1968; courtesy Carmen Lamanna Estate

N. E. Thing Co, February 20-28, 1969. Photo: Ron Vickers Ltd.; courtesy Carmen Lamanna Estate

David Rabinowitch, April 16 - May 5, 1970; courtesy Carmen Lamanna Estate

Royden Rabinowitch, January 2-21, 1971; courtesy Carmen Lamanna Estate

Ian Carr-Harris, Tony Cooper, Robert Fones, Colette Whiten, September 16 - October 5, 1972. Photo: Rick Porter; courtesy Carmen Lamanna Estate

Ian Carr-Harris, September 22 - October 11, 1973; courtesy Carmen Lamanna Estate

Murray Favro, November 24 - December 13, 1973; courtesy Carmen Lamanna Estate

General Idea, Reconstructing Futures, December 10, 1977 - January 6, 1978. Photo courtesy General Idea

Part 5

Writing by Carmen Lamanna

Part 6

The Critique of Carmen Lamanna

Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge, Carmen Lamanna, 1977, panel 1; courtesy Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge

Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge, Carmen Lamanna, 1977, panel 2; courtesy Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge

Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge exhibited at the Carmen Lamanna Gallery. This double panel work was shown in one of their exhibitions there. The photostat text below is by Condé-Beveridge; that above on each panel are magazine pages from Queen Street Magazine (Spring/Winter 1976-1977) with text by Carmen Lamanna originally published in the 1974 catalogue The Carmen Lamanna Gallery at the Owens Art Gallery.

Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge’s Marxist critique of Lamanna was of its time—though more pertinent to its sources in New York’s mid-1970s art scene, where they still lived, and not necessary shared with Lamanna’s other artists, who implicitly are subject to their critique as well. But this was not the critique Lamanna eventually was known by. His lawsuits with artists who broke away from the gallery were legendary, too. So were the lack of payments to his artists. So were the roadblocks he put in place to prevent his artists working with dealers in other cities and abroad. All of this is documented in Adele Freedman’s Canadian Art article.

“He didn’t follow the usual rules of business, either,” Freeman writes. “When he started, Lamanna sold on consignment, the usual thing, taking forty to fifty percent of sales. But beginning around 1970, in addition to his commision, he characteristically claimed ownership of fifty percent—according to value—of everything an aritst produced, an unprecendented arrangment that went o n for more than two decades…. It was on the rare occasion that an artist wanted to leave the gallery that Lamanna claimed his fifty percent of that artist’s inventory.” When General Idea, for instance, left in the later 1980s. General Idea’s “alimony” payment was half their inventory.

L’Affaire Lamanna

CAROT was a tradepaper published by Canadian Artists Representation, Ontario. In its June 1977 issue it published an article “L’affaire Lamanna” by Harry Underwood on the court case between the artist Jean Noel and the Carmen Lamanna Gallery. Lamanna demanded the right of reply. It was printed in Volume 3, Number 4, March 1978.

CAROT, Volume 3, Number 4, March 1978

Part 7

The Death of Carmen Lamanna

May 19, 1927 - May 23, 1991

Kate Taylor, Globe and Mail, November 19, 1991